DeeperStory.

In January 2022 we launched DeeperStory: M2M Movement Builders Share Their Monumental Ideas. DeeperStory is a monthly essay series where a writer receives a simple prompt: identify your community and imagine a monument that reflects it. We consider community as place, history, tradition, culture, spirit, identity or however one may define it. In describing a monument to this community -- it may be as conceptual or concrete as best fits that community’s story; one may consider location, medium, theme, duration, engagement, experience and more.

Coming Soon! DeeperStory Will Be a Book!

M2M is excited to announce that the DeeperStory essay series - launched in January 2022 and shared through our monthly mailing - is now being developed into an expanded and illustrated book of essays. We are telling the story of how we developed the M2M Forever Invitation, featuring some of our most beloved past essays and newly commissioned works, and sharing participatory activities to celebrate our own communities and imagine our own monuments. A digital accompaniment will include downloadable educational guides and workshop materials. Look out for updates and reach out to get involved!

Published June 23rd, 2023.

Precious Brady-Davis

Precious Brady-Davis is an award-winning social justice advocate, communications professional, and public speaker, as well as the author of I Have Always Been Me. She is currently the Associate Regional Communications Director at Sierra Club. Prior to this role, Brady-Davis served as the Youth Outreach Coordinator at the Center on Halsted, where under her tenure she launched a $1.6 million CDC grant which provided outreach, education, and testing services to over 3,000 young African American and Latino gay, bi, and trans youth across the city of Chicago.

My community is rooted in being whole.

My monument is a purpose that comes from pain.

When your origin story is one rooted in displacement and instability, you find community everywhere; as a child, snapdragons, wood chips, and even cracked concrete embraced me. I quickly learned that security, safety, stillness, peace and unconditional love aren’t always found at home or your place of birth. I identify with those whose still voices are chiseled from pain but operate like salt—a sting to a wound but one which provides context and depth. At a young age, I chose to surround myself with a community of people who see the beauty in all things as I do.

One of my closest friends, Kenny, whom I’ve known since I was a sophomore in high school, often jokes with me and says, “Precious, you’ll find wonder in an ordinary duplex!” There’s much more complexity to the architecture, trim, detail, and scale, especially in the neighborhood of mixed housing where I grew up in Omaha, Nebraska. I am in community with those people and places from my block.

Since I was young, I’ve had a profound optimism. I was a dreamer and communicator who walked to the beat of my rhythm, prancing in my sister's heels, frolicking in the ravine, switching like royalty in the grocery store, traversing the aisles, being chastised by my Grandmother and holding court like I still do today. I was the reigning queen of four square. I gathered my sisters, Ginger and Tanisha, along with our neighbors, the Elhausens. I received a daily talking to for tenaciously landing my bike wheels on their mother’s grass, speeding up and down the sidewalk on 66th Street across from Hartman Elementary. I couldn’t wait for the moment I’d land in the Queen square—ruling and reigning over the game. It was a time to shine—in community with my block.

However, growing up the middle child of five siblings, it was easy to feel unseen, invisible. I am the definition of otherness and have been my entire life; I am short, left-handed, biracial, queer, acne prone, and curly-haired. All of those things relate primarily to my skin but not my soul. My soul was always me.

My soul has always been me. But nothing has cut so deep as being given up by my biological mother as a child—and so anyone who has a disassociation with a birth parent, I immediately feel a kinship.

These wounds affect me in many ways. For years, holidays felt numb where all I could see were my life’s worst memories repeating. I couldn't bear putting up any holiday decorations until I decided to create my own traditions. In my own home, with my own family, I cover our house entirely during the holiday season, including a menorah, a sky-high Christmas tree laden with a growing ornament collection, along with a kinara.

My soul guides me and is charged and inspired by my queer community, climate activists protecting our planet, and those who work toward justice and commit to the liberation of all oppressed people. That commitment for me is rooted in the act of community operating with agency, standing tall, giving light to multiple perspectives, and continuously building one’s sense of self.

I am empowered by those who positively shift spaces by their mere presence—whose simple gesture in the moment can connect to the divine living within us all. I feel in community with those who continually seek wholeness physically, spiritually, and mentally. I knew from an early age the importance of the power to heal.

As the years have passed, I am no longer the chastised child playing in my sister's shoes. I am the activist standing in silver high heels, with lacquered nails rooted in the position of an arched foot in stilettos and truth.

My monument is Black and curvy. My monument is intrinsic, connected, the birthright of all people to find dignity, safety, and peace in our skin.

My monument is mobile, transferable, and contagious. It is my living advocacy for the rights of all marginalized people to have visibility and embrace freedom.

My monument for my community is ever-growing and can’t be dulled by anyone, a beacon of self-love. Ultimately, it’s trust in one’s purpose to be whole.

The same power and authority I had as a child to turn a picnic table into my stage exists today. It shifts tectonic plates, birthing acceptance, and has awakened the question, what can we be when we release ourselves from the snares that bind us? Selah.

Published May 25th, 2023.

William Estrada

William Estrada is an arts educator and multidisciplinary artist, whose current research is focused on developing community-based and culturally relevant projects that center power structures of race, economy, and cultural access in contested spaces to collectively imagine just futures. He collaborates with Mobilize Creative Collaborative, Chicago ACT Collective and Justseeds Artists’ Cooperative.

My community: Chicago ACT Collective

My monument: Radical Love & Imagination

Growing up, my family of four migrated between and across communities with a lot of familial support. At the ripe age of 17 and 18, my parents Maria Elena and Porfirio migrated to Southern California to work in the avocado, orange and lime fields. They were searching for opportunities that made all the dreams they had for our family just a little closer to grasp. Over 15 years our family lived in Valley Center, California, Guadalajara and Loma Dorada, Jalisco, Mexico, and various parts of the Southwest Side of Chicago, Illinois. As a young child, the constant movement influenced what community meant, where it could exist, and our ability to build and sustain it with the people we relied on and who made us feel at home.

Community was never a physical space for me, it was constructed by the presence of people and the memories of those who impacted us. Family was a mix of biological and chosen people who inspired and reminded us to be the best versions of ourselves. It was by no means perfect, but we often reimagined and reinvented what we wanted for ourselves and our future. Community was experienced in backyards, kitchen tables, and public parks across neighborhoods, filled with joy and celebration, laughter, singing, music, dancing, food and the latest gossip. We created these sanctuaries to heal from the racist and anti-immigration ideologies we encountered in schools, at work, and in the neighborhoods we drove through and dreamt of living in. I still remember getting chased out of a park by older kids yelling at my younger sister and I to “go back to where [we] came from” or getting punished at school for speaking Spanish. I was told by adults that my parents were “criminals who were in this country illegally” or that I “would never amount to anything but a gangbanger” because of where I lived. I heard this so much growing up that I began to believe it and to disassociate myself with Mexican culture and language.

Looking back, it was our chosen family that made it bearable to grow up in spaces that consistently tried to erase and vilify my stories and experiences. There were so many moments of hardship and sadness where our community gathered for mutual aid, emotional and mental health support, shared resources, and to remind each other that we were not alone. When Immigration and Naturalization Services conducted factory raids in the late 1980’s, my family gathered to discuss safety plans, support systems, and child care in case anyone got separated from their loved ones. These meetings helped me understand what community is and our collective power in reimagining structures that helped one another. I saw the opportunities that lay between the cracks no one else paid attention to, where we could break the boundaries that attempted to contain our brilliance and possible futures.

As I continue to grow, I am reminded of the radical love and imagination that generations of people laid the foundations for us to build, heal and expand on their dreams. I think of the love, tenacity, and fortitude I see in my own children and their ability to work towards their dreams because we are surrounded by amazing people who live their dreams everyday. The life we are living now is the guide for them to see what is possible when one intentionally builds communities of care and shared collective power. We model what it looks like to apologize when you have caused harm, what it means to repair relationships, to talk about complicated feelings, to ask for help, and to be amongst people that inspire you to see the things in yourself that you didn’t realize were there.

As a member of the Chicago ACT Collective, I am surrounded by people that are actively practicing radical love and imagination. Made up of musicians, artists, parents, administrators, and educators from various economic backgrounds and walks of life, they are my community and chosen family. We move individually and collectively. Together, we are working to build a group of socially & politically engaged artists, to create forms of resistance that promote collaboration and dialogue across multiple communities, and that reflect on and respond to current and local needs identified by those most directly impacted. The Chicago ACT Collective is a constant reminder of the work we need to do to practice love in action. We must build and sustain a just future with communities we call our own and communities we have yet to join, to learn with and from each other what it means to radically love and imagine a life of reciprocity, joy, and abundance.

My monument is Radical Love and Imagination. It sounds like the laughter of friends sitting around a campfire, sharing stories. It feels like a warm and excited embrace from someone you miss. It smells like your favorite comfort food that takes you back to moments you felt safe. This monument fills you with curiosity and energy, it serves as a reminder of the love we must have to heal generational wounds, it allows us to imagine future possibles that center joy, mutual aid, reciprocity, and a deep commitment to loving each other and the land that nourishes us. We must build the future we need now, so when we begin to walk towards our dreams, we are ready to embrace them because we now have the imagination to see.

Published April 20th, 2023.

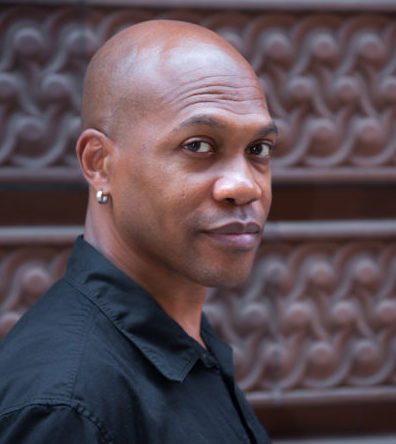

E. Patrick Johnson

E. Patrick Johnson is an award-winning scholar, performer, and educator and the Dean of the School of Communication and the Annenberg University Professor of Performance Studies and African American Studies at Northwestern University. He's the founder and director of the University's Black Arts Initiative and is a Project& Fellow. Johnson has published widely on race, class, gender, sexuality, and performance, and is the author of the award-winning books Appropriating Blackness: Performance and the Politics of Authenticity and Sweet Tea: Black Gay Men of the South—An Oral History.

My community: Black Boy Joy

Southern Borders

My community is Black boy joy—the remembrances of carefree days of growing up in the South. Like many southern towns, my hometown of Hickory, NC had a set of railroad tracks that separated the white side of town and the Black side of town. Patterned after the street system of Washington, D.C, where the streets are numbered and divided into four directional quadrants (North, South, East, West), Hickory segregated its Black population to the South and the whites to the North. The community in which I grew up was called Ridgeview and about 75% of the Black population of Hickory lived in this community. Ridgeview was a self-contained community that provided every service needed for its members, including K-12 education, a public library, community center, grocery stores, a funeral home, and an abundance of churches. And although Brown vs. Board of Education became law in 1954, desegregation of high schools did not arrive in Hickory until 1968 and primary schools were not desegregated until 1973.

Given the context of this segregated landscape, Blacks in Hickory—my family included—learned to negotiate the different border crossings demanded of us, which also shaped our conceptions of race and class. For example, many Blacks—especially women—were required to venture to the north end of town to work as domestics. My grandmother worked as a live-in domestic worker for over 18 years and my mother also worked as a domestic worker off and on for over 20 years. In the case of my grandmother, her journey to the “white folks’ house” always had an emotional impact on our family. My grandmother’s children, although adults with their own children, expressed dismay at my grandmother having to spend holidays taking care of white charges rather than spending time with her own family. Nonetheless, they also recognized that her sacrifices provided economic stability for the family as the white family for which she worked often gave her hand-me-downs that provided furniture and clothing for our family. In one instance, it also provided shelter. Familial relations, as well as race relations, hinged on economic ones. In other words, the familial dynamics within our family—and countless other families in my community—were prescribed to an extent by the labor economy that necessarily positioned, in this instance, Black women, as the “bridge” between the white folks for whom they worked and the Black community in which they lived. These economic and social relations became the ground upon which generations of Black folks in Hickory traversed. How they came to “know” the other was by crossing into that world daily—literally crossing the tracks—and bringing that knowledge back home.

I have a special relationship to the railroad tracks in my hometown because of the way this physical border linked geography to performances of race and gender. Crossing the railroad tracks to go to the movie theater with my brothers when I was a child is a case in point. Based on what our grandmother and mother had told us about being conscious about our behavior on “that side of town,” three of my older brothers and I knew that we had to perform deference when we went to the Carolina Theater on 1st Avenue NW, especially since along the way we, as Black boys, were subject to harassment from the police or other whites. Because of the potential danger, we were never allowed to go to the movies at night and many times only to a Sunday matinee. The trip to the Carolina Theater entailed us walking a mile, starting out on South Center Street, which became North Center Street once we crossed the railroad tracks and Main Avenue. Walking through our neighborhood, we would horseplay, my brothers, much older than me, running ahead of me and making me chase them down. They were not fearful of leaving me behind in our community. Once we approached the railroad tracks however, my brother Gregory, five years older, would take my hand and hold it until we reached the theater. My brothers’ comportment became more controlled, their voices less boisterous, their demeanor more serious. We had transgressed a threshold that placed us in “enemy” territory that required that we circumscribe our behavior, paradoxically, in order to find pleasure in the other’s space—the movie theater. Our movement across town and across racialized boundaries and borders necessarily required the embodiment of racial knowledge of self in the other’s eyes—a knowledge that compelled a performance of self to secure survival on two levels: namely, that we remain out of harm’s way, but also that our race and gender not bar us from the pleasures of childhood that are necessarily bound to trips to the movies.

When I travel home to see my family in Hickory I often go downtown—always by car and never on foot as I did as a child—across the railroad tracks. A freight train carrying goods still traverses this set of tracks, this monument to historical and present-day segregation. But as with all such borders—real or imagined—these tracks track my own complicated relationship to home, to myself.

Published March 20th, 2023.

Sam Kirk

Sam Kirk is a multidisciplinary artist, who explores culture and identity politics. Her artwork focuses on a call to celebrate differences and enact social change. Similar themes of uplifting and highlighting those who have been historically underrepresented and marginalized, are underscored in her recent curatorial projects such as Citizen, which is on view at the Lubeznik Center for the Arts through June 16, 2023. Kirk has been featured in publications such as Travel and Leisure, O Magazine and Forbes for her public art and global collaborations.

My community: A Band of Compassionate Leaders

My monument: Unconditional Love

Snuggled into a ranch house under the hills of Kanab, Utah, I am in a moment of reflection. Possibly my first true break since the Pandemic began, I am among a small tribe of some of the most genuine people I know. I am fortunate. With more than a decade of friendship between us, we are part of a larger network of individuals who impact the world through our work and spirit. Professions spanning the gamut between creative entrepreneurs, medical practitioners, spiritual guides, tech wizards, our common—an unwavering desire to lead with our hearts.

Throughout most of my life, I was taught a conditional form of love. It had many boundaries and rules tied to the beliefs of tradition, religion and survival. Over the years, I’ve felt less connected to this form of love. I recall wondering if it was just the city I was in, where segregation molded the people into a mindset that created barriers, or if this limitation was everywhere.

I grew up in an assimilated family. We didn’t have many traditions beyond celebrating common holidays. I regularly found myself longing for more. I wanted to understand why my mouth watered for flavor and my ears craved rhythmic beats.

I began to travel in search of traditions that connected me to my roots. I started in the neighborhoods of Chicago. Learning my cultural heritage through peers and strangers became a fascination. The more I ventured, the more I learned about the deep connections built between families and neighbors, often because of similarities. I was amazed how interwoven traditions were between different cultures—how my grandfather in Puerto Rico dances a similar bomba to my wife's mother from Costa Rica, how her cooking has similar flavors as the cuisine a friend’s mother prepares in the Gullah Islands of Beaufort, SC. This led to a deepening desire to engage people globally sharing similarities, building relationships, learning old traditions and creating new ones.

In 2018, I went to Casablanca, Morocco to paint a mural, l ended up staying for a month. The women living in the building where we were painting, eagerly awaited our arrival on their floor, giving us home-baked cookies and mint tea from their windows. My wife emphasizes the importance of welcoming guests with delicious food made with love, and in our kitchen. This generous gift to others was passed on from her mother and grandmother, and this gesture from the Moroccan women was so similar and familiar—unconditional care.

These experiences were wonderful, but I found myself still longing for a community that was a bit more accessible. I realized I wasn’t paying attention because they were right in front of me all along. I had conditions and cycles that I had to break in order to see the community that was by my side this whole time.

This band of compassionate leaders, our commonality shares a deep care for people, appreciation of culture, and the future of our world. Our careers don't usually align, our ethnicities are varied, and most of the time we are at a distance geographically, yet year after year we remain connected. For some of us, our personal connections are what bind us, for others personal and professional overlap - exploring new methods of incorporating our talents and wisdom that benefit the occupants of this universe. We work to make a positive impact in this world, hoping the remaining feeling is unconditional love.

We gathered in Utah supporting a fellow friend running a half marathon through Zion National Park. It made sense, for this particular group, our common thread is identity, nature-loving, culture-loving, people-loving, people. For the past week, we have been exploring lands unfamiliar to most of us, hiking trails and canyons that feel other worldly. We have been challenged mentally and physically, pushing our bodies to their limits, always looking out for each other. My wife and I have added a unique element to the trip, a 7-month-old baby. We managed to hike up hills, through sand and ice, for hours and literal miles. Everyone offers their help with tummy time, feedings, singing, laughing. It took decades to find it, but we have a “village.” It's an experience that is both healing and nurturing. Loving unconditionally is a practice of its own. For me, it means letting go of expectations, being present, spending time, and acknowledging every second of breath. In this moment, it's also appreciating the land we walk, the resources we have been gifted, and meals shared with stories of our past and present. We are building new traditions that will ultimately help us to be more grounded in who we are and the work we share with the world.

Published February 15th, 2023.

Ebony Reed

Ebony Reed is Chief Strategy Officer at The Marshall Project, a national news nonprofit, which covers the criminal and legal system in America. She has been ever more focused on not giving up since her longtime partner, sports journalist Terez A. Paylor, unexpectedly died in 2021. Ebony teaches on the wealth gap at the Yale School of Management, and with co-author Louise Story, she also writes a newsletter and is completing a book on this topic for HarperCollins.

My community: The Club of Resilient People

My monument: Unwavering Support

Hundreds of female journalists gathered in January for The Newswomen’s Club of New York awards program, to celebrate some of the best work that New York-based news organizations produced in the last year. We celebrated the resilience of journalists past and present. We honored women who didn’t give up in their pursuits to lead investigations and uncover and report the news, even when the odds were stacked against them.

The event marked the Club’s 100th anniversary as journalists who were honored had reported on the fall of Roe v. Wade, labor shortages, the war in Ukraine, and the role of private equity in the autism-therapy industry. Honorees shared stories not just about the work, the journalism, but about our lives as women too. Industry colleagues received awards, some bearing the names of trailblazing journalists including Nellie Bly, famously known for going undercover in a New York City insane asylum in 1887, and Ida B. Wells, who investigated more than 241 lynchings of Black Americans in the late 1800s. “You are making a difference in real time every single day,” said New York Governor Kathy Hochul, the state’s first female governor, in addressing The Newswomen’s Club of New York. “After 100 years you are still gathering. You are still a force.”

And as we celebrated each award recipient – the community grew with every high five, text message and hug – I thought about the richer, deeper community of people who persevere through extremely trying circumstances. I’ve spent more than a third of my career on the East Coast, but now as a Kansas City, Mo.- based news executive, I found the night’s fellowship strikingly familiar. It reminded me of a recent gathering of my Midwestern friends – some of us meeting for the first time since the pandemic interrupted and reshaped our lives. Like the Midwestern gathering of women at my home, this one in New York also had resilient trailblazers.

And I wondered …

How did they (how do we) do this?

What separates some of us from those who fold early in a challenge?

Is it a strong support network?

Differing degrees of determination?

More resources?

Wired this way?

And if we want to change and grow our determination, how do we actually do that?

I don’t know all of those answers, but I do know that I belong to the community of determined people.

That night in New York, I thought of women who were the first in many areas of journalism. I thought of women of color who were the first of their gender and race to enter newsrooms, make editor ranks, hold executive roles and eventually become company owners. I thought of those who achieved, yet were not celebrated. Where is the monument to those trailblazers, and moreso, the monument to their determination?

We know news organizations still need far greater gender and racial diversity. According to Reuters Institute, only 23 percent of top editors across the 200 major global news outlets are women, although 40 percent of journalists in the top ten markets are women. My community will tell you: we haven’t given up.

This community of the continuously determined transcends race, age, gender, sexual identity and geography. Our spirit and camaraderie is a monument to our work, ourselves and our futures. When we face a tough moment, we survey the entire situation. We strategize. We adjust, if necessary. And we then move forward with our plans and crew. That’s what makes us unique.

My community of fearless sisters includes my aunties, my grandmother, my late partner’s mom, Ava, colleagues, close and new friends and my strong grief and life transition counselor. They held me up when my longtime partner, Terez A. Paylor, a national NFL journalist, died in 2021. They supported me at 3 a.m. when I couldn’t sleep, struggled to carry the trash solo on Wednesday mornings in Kansas City and needed a cheerleader on life anniversaries and holidays. They’ve given me gentle pushes on my still blooming career aspirations. Those who know grief understand it does not diminish overnight. It is a long-term process of moving forward while also celebrating the love and life of those we lost. My crew’s support runs deep and has helped me rebuild, strategize and keep living.

So the next time you face obstacles, remember the club of determined people is open for membership. Our monument, our camaraderie is for everyone.

Take a moment. Look around, taking stock of your crew when you face challenges. If you need to build a new monument that’s O.K., too. And then - together - make your plans and move forward.

Published December 15th, 2022.

Ai-jen Poo

Ai-jen Poo is President of the National Domestic Workers Alliance, Director of Caring Across Generations, Co-Founder of SuperMajority, Trustee of the Ford Foundation, and a M2M Movement Builder. She is a nationally recognized expert on elder and family care, the future of work, gender equality, immigration, narrative change, and grassroots organizing.

My community: Caregivers.

My monument: A Home.

When I first met Kelly Leonard, he was not at all what I expected. It was a blind lunch; we were introduced over email by a mutual friend after I had moved to Chicago and mentioned in passing that I didn’t know anyone and found it tough to build community in my forties. I didn’t know exactly what to expect, but I immediately felt at ease upon meeting him; he was upbeat, curious, somehow both brilliant and humble, and of course, funny. I say, of course, because for over a decade, he helmed Chicago’s world-renowned home of improv comedy, Second City, and helped to make it the cultural force that it is today.

In the first part of the conversation, he talked to me about the many creative ways he and his wife Anne Libera were applying the theory behind improv to solving major social problems and gathering data on the magic of the two words, “yes, and.” Deeply inspired, I shared about my advocacy work to support caregivers: both the care workforce and family caregivers who were caring for disabled, ill or older loved ones in need of assistance. We came from such disparate fields, and yet immediately, light bulbs started going off for both of us: the collaboration the problem-solving posture, the idea that every individual within an improv group simply stays present and builds on one another. We each bring our unique tool to the project, like building a home: it comes together because we’re in it together. These ideas could be so beneficial to how we understand caregiving, both in addressing the loneliness epidemic among caregivers and in the outcomes for those relying upon care.

Together, as a partnership between Second City and Caring Across Generations, led by Anne Libera and Ishita Srivastava, we developed a training: Improv for Care. Groups of caregivers, working together, learned about how and when to deploy “yes, and,” how caring for a loved one with Alzheimer’s could be radically transformed by the simple shift from correction to acceptance. And by treating the act of caregiving as a collaborative one, not a solo endeavor. More than anything, like improv, caring is an act of presence for those relying upon your care. All who are a part of your group, each playing their different roles, add up to building a home—a safe place where each of us, across age, race, and ability are supported to live full lives, including to care.

Not long after we developed the Improv for Care training, Kelly and Anne’s young daughter Nora was diagnosed with cancer. At age 16, the fight for her life became the focal point of their lives. And, true to improv, and to the training, they invited us to be a part. We followed Kelly’s daily updates on Facebook, we knew about Nora’s good days, and the days that may as well have been torture. And it began: the hammer and nails, the beams and the insulation, the fixtures, the music and the measuring tape; the balloons, the video messages from famous comedians, the music and the meals, the space to cry out the pain, the room to laugh and feel joy despite it all.

As a monument to my community of caregivers, I would build a tiny-home in the form of Kelly and Anne’s home, made of pieces of homes from 530 caregiving families, representing the 53 million family caregivers whose experiences of care are both as varied and universally valuable as the pieces of home they contribute. People could look inside through the windows and walk into the structure to be immersed in the power of care, how it is the invisible, supportive infrastructure of our lives, and how so many of us are a part of the story. In the middle of the family room, there would be a basket for people to leave the names of someone in their lives who have cared for them or they have cared for as their contribution to the monument.

We lost dear Nora. But the house remains. And Kelly and Anne, well, they remain the scientists behind the magic of improv, but in the years since that fateful lunch, we uncovered a secret together: the strongest natural material of builders is care.

Published November 11, 2022.

George Goehl

George Goehl is a long-time community organizer, and a M2M Movement Builder. This year, he has been on the road meeting with working class people from across the political spectrum to understand how they are making meaning of this period in American life. He is the host of the documentary style podcast, To See Each Other, which follows the story of rural people coming together to fight for social justice, and the Fundamentals of Organizing, about the craft of community organizing.

Their Contribution is Not Forgotten

I’m on the train from Chicago to Michigan City. It’s a tradition. I’m going to meet my childhood friend, Jonathan; we meet up every year or so to go see America. To exactly where, we don’t know. At least not yet.

I hop off the train and toss my backpack in the trunk. After an awkward hug, Jonathan and I spread an Atlas across the hood—which direction this time? In the end, any will do because all we want is to know our country and its truths. Not through the pen of journalists or the camera of filmmakers, but through us, being up close, in the cracks.

We head to Ohio, where my people settled. We all know of the rustbelt, of industry long gone, and the loss of livelihood. Still, until you are really there, it’s hard to imagine how much remains that will remind you of what once was. The iconic companies that called these towns home, do not neatly pack up—they just go. They leave vacant factories the size of football fields and neighborhoods once brimming with life, now ghost towns for miles.

It’s a story I know well. I grew up in Southern Indiana, first in Medora, a town of 900. We lived next to the county lumberjack, Otis and his wife Flossy, and across the road from the county dump. It may not sound like much, but those were the happiest years of my life.

The last 30 years have been rough on Medora. Since 1904, the Medora Brick Factory employed a workforce of 50 people. In a town of 900, that’s a lot of jobs. In igloo shaped kilns, local Hoosiers worked around the clock to knock out 50,000 handmade bricks a day. The plant shut down in 1992, ending a nearly 90-year run of proudly supplying bricks to cities and towns throughout the Midwest.

A few years later, an automotive parts plant that employed hundreds moved overseas. The good jobs, and the meaning they provided through what workers built together with a close community of people, were replaced by meth labs and opioid addiction. In places that once thrived, the people who remain are left to make meaning of their current lives. Now what?

I’ve felt this close-up. A few summers ago three friends back home died of despair in a matter of weeks. One of my closest friends lived in a shack with no plumbing. He overdosed. Another drank himself to death. One friend who had been homeless much of his adult life fell asleep and never woke up. Each struggled to live up to the American ideal that the next generation does better than the last.

People feel unseen, it’s something we all share. My work as a community organizer has taught me that people in communities that once thrived but are now fighting to survive feel newly forgotten. There’s an acuteness to it.

I want there to be monuments in Medora, Indiana, Youngstown, Ohio, Flint, Michigan and other struggling post-industrial towns that celebrate the people who got up each morning, or came in well after dark to work the graveyard shift, to build things that we needed.

When I pull into a struggling town to meet with people who want to organize, I would like to see something as simple as this.

For five decades, workers of all races came into this plant three shifts a day and made millions of tires so the rest of us could get to where we needed to go. They organized for better wages, improved the way the work was done, and were the backbone of this neighborhood. Their contribution is not forgotten.

We could even go further and clearly name why these companies left town:

This is the result of an economic system in which big corporations sew division across racial lines, maximize profits by any means possible, and leave town the minute they find a cheaper way to get the work done. The people who remain behind, against all odds, must make things whole.

Until we see honest history, I try to find the truth in what remains; if you look and listen it is all there. The abandoned and unsecured remains of industry howl of hasty departure and reckless neglect. Each empty house along a deserted street is a monument to a broken dream. Still, there is beauty too. The quality craftsmanship of workers and the ingenuity of designers and engineers is still on display, years later. As roofs cave in, new light comes in, and the graffiti of neighborhood kids bears new color. Machines constructed by everyday people weather in wondrous ways. The complexion of those handmade bricks transforms as lichen digs into the pores. Limestone blocks pulled from the ground by stonecutters react to abandoned chemicals eating away at their surfaces, stones that formed millions of years ago.

Until new monuments are built, weather and time, past and present, work together to tell the story, and the whole truth. In the meantime, I sit with the tension of whether enough people see the same truths that I do, because the meaning we make will have a lot to say about where we go from here.

Published September 22, 2022.

Todd Lawrence is a PhD., Associate Professor, English and American Culture and Difference, University of St. Thomas. Todd is Co-Director of Urban Art Mapping Project, which is the lead collaborating organization on The M2M Archive.

Todd Lawrence

This Place is My Home

For most of my childhood, my family lived far away from our relatives and hometown. When we came home to visit, the house where my paternal grandmother lived often served as our homebase. The small yellow house, rebuilt three times after fires, and packed full of my twin uncles’ comic books, family picture albums, and boxes of papers, became a familiar mystery to me. I knew every corner of it, but was always confused by the photos of people I had never seen before or documents with names I didn’t recognize.

Sometimes, my grandmother would pack my cousins and me into her car and drive us out to the country, to a small, slowly-rotting church sitting in the middle of nowhere. Tall fescue crowded around it, hiding in the un-mowed grass, I was sure, gangs of snakes, spiders, and anything else that might easily kiss off a toe, foot, or entire leg. The building itself was brown and faded, its wooden siding weathered by years of rain, wind, and snow. Inside, the floor creaked as we crossed it, threatening to cave in and swallow us up under years of dust and grime.

I didn’t understand why my grandmother brought us to this church. When my older cousin Joi would ask her, she would say, “This is my home.” We’d ask what she meant – what about her house? “This is all that’s left of Pennytown,” she would tell us, “This is where I was born. This is where you come from.”

My grandmother, Josephine Robinson Lawrence, worked to save that church, the last standing structure of the all-Black community of Pennytown, MO. With her small house as her headquarters, she raised money, asked local churches for support, gave talks at libraries and schools, and consulted with university professors. In 1988, she was finally able to have the church placed on the National Registry of Historic Places. In 1996, her hard work paid off when the church was renovated – taken apart and reassembled brick by brick in a painstaking process. My grandmother never lived to see the church completed. She died of cancer in 1992 at the age of 63.

Pennytown is just one of many towns established in the Midwest by free Black people from the 1870s through the 1940s. In many cases, Black folks left those towns in the 30s and 40s, moving to larger cities to find work. My Auntie, Virginia Houston, was the last child born at Pennytown in 1944. Fittingly, she took over the work of her mother and has become the principal advocate for preserving the memory of this once bustling Black hamlet in central Missouri. The Pennytown Freewill Baptist Church stands as a monument to the many Black folks who lived in that community.

It's been forty years since my grandmother took us to Pennytown on that day that remains in my memory. It’s taken me years to understand what she meant when she told us that dry patch of farmland was where we came from. In my work with folks from another Black town in southeast Missouri, Pinhook – a town destroyed by the intentional breaching of a Mississippi River levee – I learned what place can mean to a community. The people of Pinhook taught me that community can be maintained even when your home place has been lost or destroyed. One special person told me, “Pinhook is in our hearts. Wherever we go, it will be with us.” This is why they continue to gather each year to celebrate “Pinhook Day” even though no one can live in their beloved town anymore. It is the same reason why descendants of Pennytown return to our church every first Sunday of August for our homecoming. It’s the reason for thousands of traditional Black homecomings – Black folks coming together to remember, memorialize, tend to, and preserve monuments of community.

These places are vital and must be preserved. But over the years I have learned that it is what happens when we gather at these places – the laughing, sharing, storytelling, mourning, welcoming of new, old, and returning community members – that is the monument. So, while our monument to our ancestors – especially my dear grandmother – is indeed a building we work hard to preserve, its true meaning is only clear to me when I hear the sounds of singing spilling out of its doors.

Published June 9, 2022.

Kamal Sinclair is Principle Collaborator in Sinclair Futures, a family creative practice, formerly Executive Director of the Guild of Future Architects, and Director of Sundance Institute’s New Frontier Labs Program.

Kamal Sinclair

My community is fractal. It repeats its basic patterns across scales of geographic, identity, affinity, functional, and disciplinary groups. It scales from the people living in my home to those living on the planet, from ancestors to progeny, human and non-humans, and from physical to virtual to metaphysical space. Also, my community is flawed and perfect, a source of pain and wellness. It requires me to acknowledge complicity in the poor action it's taken and will take, as well as the great victories of justice and healing it has won and will win.

Can a monument to my community capture all this?

The conventional notion of a monument is a monolithic mass tied to a static spot of earth, shaped into a timestamped and unchangeable form. However, when we shift our perspective from a pedestrian to an atomic scale, we understand it is actually mostly empty space shaped by a delicate attraction of individual atoms. Each atom is held into shape by a nucleus dynamically circled by negatively charged electrons and positively charged protons, with even smaller sub-atomic structures at the quantum scale. And if we shift our perspective to a macro scale we understand it is actually a single point on a constellation of points that outline a larger shape.

As a cis-gendered, straight, woman from a low-income or crisis-income neighborhood in Los Angeles, with a small Persian religious background, with DNA from ancestors on the small islands of Britain and Ireland, and the much larger lands of West Africa, I can’t help but see community as many things.

Perhaps a monument to my community provokes viewers to shift their scale and angle of perception, to see past the illusion of it being one static thing?

I love the experience of physical materiality in these kinds of expressions. I love walking through places with statues, murals, totems, designed old-growth landscapes, and living monuments, that represent thousands of years of community’s experience, evolution, and de-evolution, I’ve imagined the atoms of my feet vibrating with the atoms of the ground they walked on, the ghosts of their daily lives filling the space. They make me reflect on my own fleeting life and help me make meaning of my limited days.

Perhaps a monument to my community is made of a blend of physical and virtual materials? A prism in space that unlocks a myriad of digital images, sounds, voices, and forms that illustrated the presence of those ghost stories, or geographically dispersed prisms that unlock the invisible map of stories and relationships between the different facets of my community. Moments of action that can be viewed from different individuals' perspectives, including ways they can be polar opposites in their interpretation, but with many other perspectives that fill in the gaps in that understanding between two binaries.

Perhaps they actually start to feel the atoms of their feet vibrating with the atoms of the ground that bore the actions and lives of my community and by virtue of their visit they leave their own ghost movement.

That might be a monument to my community.

Published April 3, 2022.

Tiu is the founder and host of the podcast, "Know Them, Be Them, Raise Them," a show that informs and inspires mindful and growth-oriented moms of girls. She's an attorney, educator, philanthropist and mom to two daughters.

CARMELITA (CAT) TIU

Every day, people make the difficult decision to leave their countries in search of better lives.

My parents made that decision in 1965, fresh out of med school. The U.S. had a shortage of medical professionals and was eager to sponsor them. They came hoping to use their skills to serve, provide financial support to family in the Philippines and raise a family in a country where it seemed like success was only limited by one’s willingness to work and one’s imagination. They checked all three boxes. Nearly 20 years later in 1984, they beamed with quiet pride when they were sworn in as citizens—intensely aware of the privilege, promise and responsibility of being American (they have never missed an election).

The journey looks different for others. Three of my cousins gambled on marrying into U.S. citizenship. One fell for a man that was paid to marry her; they’re still together. Another’s marriage was a business arrangement—she’s now a doctor and he’s a footnote to her twenties. The third landed in an abusive marriage that endured for years. Others leave even more to chance, slipping into a vulnerable undocumented limbo, having to pick up jobs that others refuse to do. Some land in stable situations; many don’t.

For those who are generations away from foreign-born relatives, these stories, plus faceless statistics and an imbalanced media diet, can evoke feelings of scarcity and fear. Harmful stereotypes conjure images of immigrants as an insatiable, lawless, anonymous mass, preying upon the U.S. and its resources.

But for those of us who have lived the stories of immigration it is a different reality. We know the cost of leaving: family and friends left behind; a shadow of “otherness;” feelings of displacement that may never fade. Degrees, family names, titles and prestige rendered worthless on U.S. soil. We know why the price was paid: Possibility. Hope. Opportunity.

I am inspired by the idea of a Monument to Hope and Possibilities. A monument to those who choose the struggle to become American. To me, Hope looks like love locks on bridges, Chinese lantern festivals, prayer walls…and perhaps, immigrant dreams written on strips of paper, tied to fences and structures near hubs that routinely greet newcomers. International arrival terminals, bus stops, train stations, community gathering spaces. Intentional, accessible, participatory, hopeful.

I see thousands of wishes and whys crowding the fences—monuments in constant flux, like our country, as new desires are added and old ones fade. A vibrant explosion of optimism, fluttering as people pass by. A reminder of the dreams that motivate us, surround us and bind us. Hope and yearning—uniting us all.

Community, for me, begins with our innate capacity and proclivity to be intimate with “the stranger” or “strange.” At birth, this capacity to connect with the unfamiliar is stunning; most of us, for example, have the ability to adapt to any of the 7000 languages that connect communities around the world. What might now feel like strange or unnatural utterances, clicks or tongue movements, was once well within our reach. This says something not only about our adaptability but our inclination for connectivity. In this way, we all begin with a radical and embodied openness to “the other,” whether human, earthly or celestial. This has been at the heart of my life, my sense of community, and how I feel about the world; it is this force that should be monumentalized in the everyday.

I feel that cultivating this capacity into sustainable communities with “the other” relies utterly and entirely upon conditions of care. Western societies devalue reproductive labor as supplemental feminine work. But I have found when we nurture, nourish and center non-exploitative and non-extractive relations of care, we have grounding and soil from which we can grapple with the inevitable conflicts, precarity and suffering that life brings. Communities—my communities in particular—are dependent at their core on healthy food, cooking, cleaning toilets, child and elder care, nursing illnesses, fostering wellness and securing safe housing. When we center these domains of life, nurturing these labor practices into ecologies of care, all relations transform accordingly.

I also believe that sustained and supple connectivity depends upon an embodied commitment to divergent orientations. Whether a community comes together for a fleeting period or over several generations, whether it is comprised of evacuees or mycelial networks, whether it is surviving trauma or being queer, we must develop tools and dedication to work with our different temporalities, environmental conditions, histories, generational trajectories and privileges. The expectation that our communities become a monoculture works against the reality, health and ultimate sustainability of togetherness and love. Love matters to me the most—it turns out that love is crucial to do anything that is very difficult.

I feel we need to weave the erotic through our relations with the familiar and the strange. Audre Lorde argued that for oppression to thrive, it must corrupt our connectivity and intimacy not only with others but with ourselves. In erotic practices and ecologies, we are no longer alienated from our intuition, joy and deep sensibilities. Rather, we nourish our earliest capacity for joyful and ethical togetherness.

I’m improvising my life and love as I go, expanding community and expanding love. This communal process itself is worthy of a collective monumental gesture.

Published January 27, 2022.

SUHAD BABAA

Award-Winning Film Producer, News Publisher, Human Rights Advocate, Executive Director of JUST VISION

Dr. Tremmel is an interdisciplinary scholar and artist whose work explores spaces of play and pleasure as historically significant sites of social struggle and knowledge production. He is currently a professor of history and gender and sexuality studies at Tulane University in New Orleans, LA.

DR. RED VAUGHAN TREMMEL

The question of how to define home and community has always conjured a certain kind of uncertainty in me. That might be because of the rare blend of my family. First-generation Palestinian, Korean, Muslim, and Christian. It may be because my orientation is a queer one, both in who and how I love, but also in how I engage and see the world. And, still, it might be because I carry generations of colonization, of displacement, of uprooting, and of erasure that continues until this day.

But several years ago, writing to a friend, who I understood my community to be was clear:

My people are those with deep wells of compassion, of courage, of self-reflection, of tenacity. My people are people who take great effort to write words with care, and similarly speak words of love and care, because they know that words carry tremendous power. My people are those who call and act for change when there are injustices around them, even when they are swimming against the tide.

It’s no surprise that for over a decade, with the Just Vision team, I have been documenting and amplifying stories of courageous people like Mohammed El Kurd, a young man who grew up in the Palestinian neighborhood of Sheikh Jarrah in occupied East Jerusalem. Recently, speaking at the United Nations, he spoke of the crossroads where we stand today with so many of the inequities and injustices of our lifetime:

“When we reflect back on atrocities today, we think about them with so much moral clarity....We forget that when these atrocities were happening, they were perfectly legal….controversial, contested, too complex. We all think that had it been us then, back there, at that point in time, we would have been on the right side of history.…”

The reason I do what I do is so that the pain, courage, and resilience of our many communities in struggle are not left to the pages of our history books, past tense. Just as I wish that monuments that lionize oppressors are re-imagined, memorials, museums, and statues erected after the fact are not the monuments I wish for any of our communities. I want monuments that remind us of the best of who we can be. Monuments that inspire others to act courageously in the here and the now. Monuments that embody movements.

Published March 1 2022.